Buffalo Spree: December 2025

A big thank you to M. Delmonico Connolly & Buffalo Spree for this article about Rodney Taylor’s life and work and to Annette Daniels Taylor & family for their trust.

Rodney Taylor: A Living Painter, Rivalry Hosts a Legacy Exhibition

By M. Delmonico Connolly

ON A LOOSE sheet of paper among artist Rodney Taylor's journals is a quadrant made in watercolor, a word written in each square: Hope. Death. Life. Pain.

After a life devoted to family and art, Taylor passed away in December 2019. He had kidney disease. Two transplants. Four kids. A wife. In January 2020, his first showing at what was then Albright-Knox Art Gallery (AKAG). And now, a solo show, Rodney Taylor: The Burden of Water, runs through December 19 at Rivalry Projects. "His voice deserves to be part of today's cultural dialogue, not only for what it foresaw, but for the empathy, clarity, and complexity it brings to the question of where we go from here,” Rivalry Projects owner Ryan Arthurs and director Olivia McManus offer in a statement.

As a kid, Taylor was obsessed with comic books and illustrations. Middle school found him on the basketball court. If he wasn't playing himself, he was watching his friends and brothers play, drawing them and offering the results for sale afterward.

Taylor's parents didn't always know what to make of him and his art, but they didn't discourage him. His father, the first Black x-ray technician in Buffalo, brought home radiographic film for Taylor to paint on. And his parents took him to AKAG.

In his journal, Taylor wrote of roaming the galleries until he came to a Chaïm Soutine painting still on display there, a slab of hanging beef: "I stared for quite a long time." Taylor also worked at AKAG as part of the mayor's summer youth program; he would go back often throughout his life.

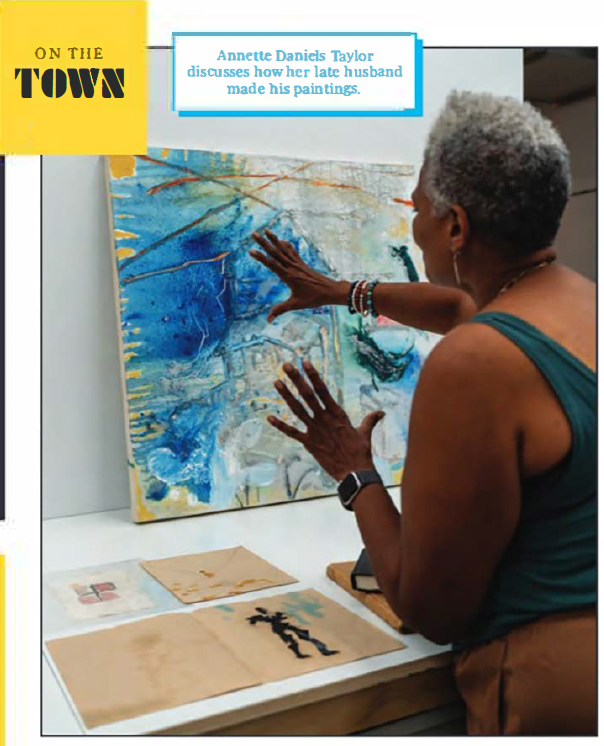

"He wanted to figure out what it was to be an artist and how you become an artist and why you would be an artist," says Taylor's widow and theater artist/author Annette Daniels Taylor.

Taylor applied to New York's Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) to study illustration; he didn't get in . His work wasn't as strong as other candidates' he was told. So Taylor took art classes for the next year at Villa Maria, finding something there that he'd chase the rest of his life: people to talk to about art. When he reapplied to FIT, he was accepted.

Taylor's dad drove him to the bus stop, handed him a mayo jar full of change, and told him, "Good luck:' At FIT, Taylor majored in illustration for a year before switching to fine art. A year later, when his painting started getting him shows, he dropped out.

Jobs at fine art brokers-businesses you might I call to get art for an office or lobby-followed. These sales jobs had Taylor dressing in suits, nice shoes, and practicing the fine art of persuasion and also visiting lots of artists' studios, every visit a chance to learn. His next job was as a barista at Angelika Film Center, where Daniels Taylor — who'd woken dreaming of cappuccino-landed in his line. "He made me a cappuccino," she recalls." And then we exchanged numbers and started seeing each other." Six months later, they were married.

At the time, Daniels Taylor worked in costume and fashion styling, the first steps toward a career as a theatrical writer/director/actor, and the pair of artists sought to make a life, together and in the arts.

They acted as partners, supporting each other and understanding each other's need for both time and independence in service of their art; it required both commitment and trust.

"If one of us was not going to get a regular nine-to-five office job, then our finances were going to be low, and there were going to be things that we may not be able to do that our peers were doing," recalls Daniels Taylor, who notes things got even trickier once children arrived. "But we understood what our goals were, and so we were able to balance time."

At times, when opportunities fell through or finances imploded, someone took a job for a bit and there were teary calls to family about the stress of it all, but their desire to support each other in pursuit of their artistic goals remained steadfast.

Taylor meanwhile had begun to move from his early landscape paintings on wood, in rich browns like a Rembrandt, into paintings almost sculpture-like. He worked without gloves so he could feel the texture of the paint: cadmium red, cadmium yellow, cadmium blue. The chemical element gave those paints bright colors that wouldn't fade was also toxic in small doses.

Moved by the circumstances of the city and country, Taylor's art was political and elemental. He used clay, experimenting constantly with surfaces. "Portrait of men of color painted (encountered) by the same disconsolate, troubled detachment [as the] surface I employ," Taylor notes in one journal of work made in a "long, turbulent, anxiety-filled era."

Daniels Taylor was making moves as well. On a scholarship from New York City Housing Authority, she studied acting at the famed Lee Strasberg Theatre & Film Institute-while six months pregnant with their third child.

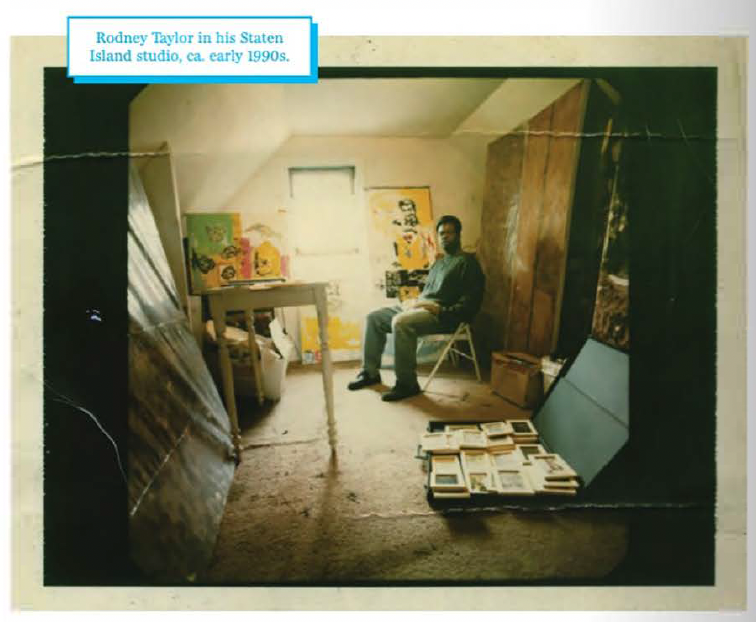

And then Taylor had passed out after running for the train. The next day, he fell in the bathroom. Doctors confirmed kidney disease resulting from the toxic paints he'd been using. On October 21, 1999, the family moved to Buffalo, where chances of getting a kidney transplant were higher. The decision prolonged Taylor's life but, to him, felt like an end of what had only just started in New York. "Buffalo needs art," Taylor wrote, "although this is not the place to sell art."

Joe Lin-Hill, former Deputy Director of Buffalo AKG Art Museum, says Taylor's life was full of hypotheticals: "If he had been able to stay in New York ... if he hadn't been sick ... if, if. .. " In 2006, another AKG curator, Claire Schneider, who helped spearhead the museum's acquisition of his work, wrote, "I believe strongly if he was in New York, he would have a dealer." Taylor had become, despite his best intentions, a hidden gem.

Even after a transplant, kidney disease takes a toll: fatigue, nausea, loss of appetite, bone pain. Taylor spent ten years in dialysis. But he never compromised, never stopped. "O.K.," he wrote in a journal. "It looks like the only way to go is to go all the way with as many surgeries as possible." In summer, he turned his home's porch into an open studio. He wanted the community to see what a painter does: paint.

In 2019, Taylor produced Home Series, where the houses seem so frail that they might scatter across the paper. Life is nothing but such fragile contingencies. There is some irony that it was only in Buffalo, not New York City, that this artistic couple could own a home for their family of six. Taylor's last works were shown in Domestic Thresholds, an exhibition at Albright-Knox Northland, a show he must have hoped for all his life-and one he didn't get to see.

Abstraction can sometimes be difficult territory. One can be tempted to look for a code that unlocks hidden meaning, but taking in a painting can be like taking in a landscape: what it means is what you see. Buffalo AKG curator Aaron Ott wrote of a work in Taylor's Home Series, "This painting teems with aggressive and unrestrained mark-making. Scribbles of colored pencil, blotches of paint, and crusts of cracked and webbed clay." Lin-Hil speaks about how for Taylor, process was the joy.

"What I hope to accomplish with this painting is a sense of loss, tragedy, human suffering," reads one of Taylor's journal entries. "They're like archaeological tablets that record moments that no longer exist."

Five years later, we have another chance to see those moments. At Rivalry, the diligent work of McManus and Arthurs ensures new attention and continuation of Taylor's legacy. "It is important to me to take my art as far as possible," Taylor once wrote. Start in a different quadrant: Pain. Hope. Death. Life.

He's still going.